Byzantine Art in General Could Be Said to Be in Relation to Christian Art

Byzantine art comprises the torso of Christian Greek artistic products of the Eastern Roman (Byzantine) Empire,[1] equally well as the nations and states that inherited culturally from the empire. Though the empire itself emerged from the decline of Rome and lasted until the Fall of Constantinople in 1453,[2] the start date of the Byzantine menses is rather clearer in art history than in political history, if nevertheless imprecise. Many Eastern Orthodox states in Eastern Europe, as well as to some degree the Islamic states of the eastern Mediterranean, preserved many aspects of the empire's culture and art for centuries after.

A number of contemporary states with the Byzantine Empire were culturally influenced by it without actually being part of it (the "Byzantine commonwealth"). These included the Rus, every bit well equally some not-Orthodox states like the Republic of Venice, which separated from the Byzantine Empire in the 10th century, and the Kingdom of Sicily, which had close ties to the Byzantine Empire and had as well been a Byzantine territory until the 10th century with a big Greek-speaking population persisting into the 12th century. Other states having a Byzantine creative tradition, had oscillated throughout the Middle Ages between being part of the Byzantine Empire and having periods of independence, such as Serbia and Republic of bulgaria. After the fall of the Byzantine capital of Constantinople in 1453, fine art produced by Eastern Orthodox Christians living in the Ottoman Empire was often chosen "post-Byzantine." Certain artistic traditions that originated in the Byzantine Empire, particularly in regard to icon painting and church compages, are maintained in Hellenic republic, Cyprus, Serbia, Bulgaria, Romania, Russian federation and other Eastern Orthodox countries to the present day.

Introduction [edit]

Byzantine fine art originated and evolved from the Christianized Greek culture of the Eastern Roman Empire; content from both Christianity and classical Greek mythology were artistically expressed through Hellenistic modes of style and iconography.[3] The fine art of Byzantium never lost sight of its classical heritage; the Byzantine capital, Constantinople, was adorned with a large number of classical sculptures,[four] although they eventually became an object of some puzzlement for its inhabitants[v] (however, Byzantine beholders showed no signs of puzzlement towards other forms of classical media such every bit wall paintings[vi]). The footing of Byzantine art is a fundamental artistic attitude held by the Byzantine Greeks who, like their aboriginal Greek predecessors, "were never satisfied with a play of forms lonely, but stimulated by an innate rationalism, endowed forms with life by associating them with a meaningful content."[7] Although the fine art produced in the Byzantine Empire was marked by periodic revivals of a classical aesthetic, it was above all marked past the development of a new aesthetic divers past its salient "abstract", or anti-naturalistic character. If classical art was marked by the attempt to create representations that mimicked reality equally closely as possible, Byzantine art seems to accept abandoned this endeavor in favor of a more than symbolic approach.

The Ethiopian Saint Arethas depicted in traditional Byzantine style (10th century)

The nature and causes of this transformation, which largely took identify during late artifact, have been a bailiwick of scholarly argue for centuries.[8] Giorgio Vasari attributed it to a pass up in artistic skills and standards, which had in turn been revived past his contemporaries in the Italian Renaissance. Although this indicate of view has been occasionally revived, nearly notably by Bernard Berenson,[nine] modernistic scholars tend to accept a more positive view of the Byzantine aesthetic. Alois Riegl and Josef Strzygowski, writing in the early 20th century, were above all responsible for the revaluation of tardily antique art.[10] Riegl saw it as a natural development of pre-existing tendencies in Roman art, whereas Strzygowski viewed it as a product of "oriental" influences. Notable recent contributions to the debate include those of Ernst Kitzinger,[11] who traced a "dialectic" betwixt "abstract" and "Hellenistic" tendencies in tardily antiquity, and John Onians,[12] who saw an "increase in visual response" in late antiquity, through which a viewer "could await at something which was in twentieth-century terms purely abstract and find it representational."

In any instance, the debate is purely modernistic: it is clear that well-nigh Byzantine viewers did not consider their fine art to exist abstract or unnaturalistic. As Cyril Mango has observed, "our own appreciation of Byzantine art stems largely from the fact that this art is not naturalistic; however the Byzantines themselves, judging by their extant statements, regarded information technology as existence highly naturalistic and every bit being direct in the tradition of Phidias, Apelles, and Zeuxis."[thirteen]

Frescoes in Nerezi near Skopje (1164), with their unique blend of high tragedy, gentle humanity, and homespun realism, anticipate the approach of Giotto and other proto-Renaissance Italian artists.

The field of study affair of awe-inspiring Byzantine art was primarily religious and imperial: the ii themes are often combined, as in the portraits of later Byzantine emperors that decorated the interior of the sixth-century church of Hagia Sophia in Constantinople. These preoccupations are partly a result of the pious and autocratic nature of Byzantine social club, and partly a result of its economical construction: the wealth of the empire was concentrated in the hands of the church and the royal part, which had the greatest opportunity to undertake monumental artistic commissions.

Religious fine art was not, however, limited to the awe-inspiring decoration of church interiors. One of the well-nigh of import genres of Byzantine art was the icon, an image of Christ, the Virgin, or a saint, used every bit an object of veneration in Orthodox churches and individual homes alike. Icons were more than religious than aesthetic in nature: especially after the end of iconoclasm, they were understood to manifest the unique "presence" of the figure depicted past ways of a "likeness" to that figure maintained through carefully maintained canons of representation.[14]

The illumination of manuscripts was some other major genre of Byzantine art. The almost commonly illustrated texts were religious, both scripture itself (particularly the Psalms) and devotional or theological texts (such as the Ladder of Divine Ascent of John Climacus or the homilies of Gregory of Nazianzus). Secular texts were also illuminated: of import examples include the Alexander Romance and the history of John Skylitzes.

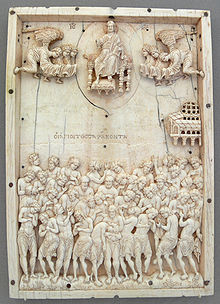

The Byzantines inherited the Early Christian distrust of awe-inspiring sculpture in religious art, and produced only reliefs, of which very few survivals are anything like life-size, in sharp contrast to the medieval art of the West, where monumental sculpture revived from Carolingian fine art onwards. Small ivories were also mostly in relief.

The so-called "minor arts" were very important in Byzantine art and luxury items, including ivories carved in relief as formal presentation Consular diptychs or caskets such as the Veroli casket, hardstone carvings, enamels, drinking glass, jewelry, metalwork, and figured silks were produced in big quantities throughout the Byzantine era. Many of these were religious in nature, although a big number of objects with secular or non-representational ornament were produced: for example, ivories representing themes from classical mythology. Byzantine ceramics were relatively crude, as pottery was never used at the tables of the rich, who ate off Byzantine silver.

Periods [edit]

Byzantine fine art and architecture is divided into four periods by convention: the Early period, commencing with the Edict of Milan (when Christian worship was legitimized) and the transfer of the imperial seat to Constantinople, extends to AD 842, with the conclusion of Iconoclasm; the Middle, or high menstruum, begins with the restoration of the icons in 843 and culminates in the Autumn of Constantinople to the Crusaders in 1204; the Late menses includes the eclectic osmosis betwixt Western European and traditional Byzantine elements in art and compages, and ends with the Fall of Constantinople to the Ottoman Turks in 1453. The term post-Byzantine is so used for later years, whereas "Neo-Byzantine" is used for art and architecture from the 19th century onwards, when the dissolution of the Ottoman Empire prompted a renewed appreciation of Byzantium by artists and historians akin.

Early Byzantine fine art [edit]

Two events were of fundamental importance to the development of a unique, Byzantine fine art. First, the Edict of Milan, issued past the emperors Constantine I and Licinius in 313, allowed for public Christian worship, and led to the evolution of a awe-inspiring, Christian art. 2nd, the dedication of Constantinople in 330 created a bang-up new artistic centre for the eastern half of the Empire, and a specifically Christian one. Other artistic traditions flourished in rival cities such as Alexandria, Antioch, and Rome, but it was non until all of these cities had fallen - the first two to the Arabs and Rome to the Goths - that Constantinople established its supremacy.

Constantine devoted peachy effort to the ornament of Constantinople, adorning its public spaces with ancient statuary,[fifteen] and building a forum dominated past a porphyry column that carried a statue of himself.[16] Major Constantinopolitan churches built nether Constantine and his son, Constantius Ii, included the original foundations of Hagia Sophia and the Church building of the Holy Apostles.[17]

The next major building entrada in Constantinople was sponsored by Theodosius I. The nigh of import surviving monument of this period is the obelisk and base erected by Theodosius in the Hippodrome[18] which, with the big silvery dish called the Missorium of Theodosius I, represents the classic examples of what is sometimes called the "Theodosian Renaissance". The earliest surviving church in Constantinople is the Basilica of St. John at the Stoudios Monastery, congenital in the fifth century.[19]

Miniatures of the 6th-century Rabula Gospel (a Byzantine Syriac Gospel) display the more than abstruse and symbolic nature of Byzantine art

Due to subsequent rebuilding and destruction, relatively few Constantinopolitan monuments of this early on period survive. Nonetheless, the evolution of awe-inspiring early Byzantine art tin yet exist traced through surviving structures in other cities. For example, important early churches are found in Rome (including Santa Sabina and Santa Maria Maggiore),[twenty] and in Thessaloniki (the Rotunda and the Acheiropoietos Basilica).[21]

A number of of import illuminated manuscripts, both sacred and secular, survive from this early on period. Classical authors, including Virgil (represented by the Vergilius Vaticanus[22] and the Vergilius Romanus)[23] and Homer (represented by the Ambrosian Iliad), were illustrated with narrative paintings. Illuminated biblical manuscripts of this period survive only in fragments: for example, the Quedlinburg Itala fragment is a minor portion of what must have been a lavishly illustrated re-create of 1 Kings.[24]

Early on Byzantine art was too marked by the cultivation of ivory carving.[25] Ivory diptychs, ofttimes elaborately decorated, were issued as gifts by newly appointed consuls.[26] Silverish plates were another of import grade of luxury art:[27] amid the well-nigh lavish from this period is the Missorium of Theodosius I.[28] Sarcophagi continued to be produced in great numbers.

Age of Justinian I [edit]

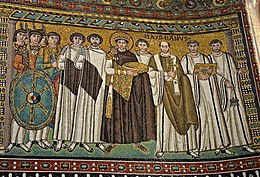

Mosaic from San Vitale in Ravenna, showing the Emperor Justinian and Bishop Maximian, surrounded past clerics and soldiers.

Significant changes in Byzantine art coincided with the reign of Justinian I (527–565). Justinian devoted much of his reign to reconquering Italian republic, North Africa and Spain. He also laid the foundations of the imperial authoritarianism of the Byzantine state, codifying its laws and imposing his religious views on all his subjects by law.[29]

A significant component of Justinian's project of imperial renovation was a massive building program, which was described in a book, the Buildings, written by Justinian's court historian, Procopius.[30] Justinian renovated, rebuilt, or founded anew countless churches inside Constantinople, including Hagia Sophia,[31] which had been destroyed during the Nika riots, the Church building of the Holy Apostles,[32] and the Church of Saints Sergius and Bacchus.[33] Justinian also built a number of churches and fortifications outside of the imperial capital, including Saint Catherine'south Monastery on Mount Sinai in Egypt,[34] Basilica of Saint Sofia in Sofia and the Basilica of St. John in Ephesus.[35]

Several major churches of this period were congenital in the provinces by local bishops in simulated of the new Constantinopolitan foundations. The Basilica of San Vitale in Ravenna, was built by Bishop Maximianus. The ornamentation of San Vitale includes important mosaics of Justinian and his empress, Theodora, although neither ever visited the church building.[36] Also of note is the Euphrasian Basilica in Poreč.[37]

Contempo archeological discoveries in the 19th and 20th centuries unearthed a large grouping of Early Byzantine mosaics in the Centre East. The eastern provinces of the Eastern Roman and afterward the Byzantine Empires inherited a strong artistic tradition from Late Artifact. Christian mosaic art flourished in this area from the fourth century onwards. The tradition of making mosaics was carried on in the Umayyad era until the cease of the 8th century. The most important surviving examples are the Madaba Map, the mosaics of Mount Nebo, Saint Catherine's Monastery and the Church building of St Stephen in ancient Kastron Mefaa (at present Umm ar-Rasas).

The offset fully preserved illuminated biblical manuscripts date to the first one-half of the sixth century, most notably the Vienna Genesis,[38] the Rossano Gospels,[39] and the Sinope Gospels.[40] The Vienna Dioscurides is a lavishly illustrated botanical treatise, presented every bit a gift to the Byzantine aristocrat Julia Anicia.[41]

Important ivory sculptures of this period include the Barberini ivory, which probably depicts Justinian himself,[42] and the Archangel ivory in the British Museum.[43] Silver plate continued to be decorated with scenes drawn from classical mythology; for example, a plate in the Cabinet des Médailles, Paris, depicts Hercules wrestling the Nemean lion.[44]

Seventh-century crisis [edit]

The Age of Justinian was followed by a political decline, since most of Justinian's conquests were lost and the Empire faced acute crisis with the invasions of the Avars, Slavs, Persians and Arabs in the seventh century. Constantinople was likewise wracked by religious and political conflict.[45]

The nearly significant surviving monumental projects of this period were undertaken exterior of the imperial capital. The church of Hagios Demetrios in Thessaloniki was rebuilt afterwards a fire in the mid-7th century. The new sections include mosaics executed in a remarkably abstract style.[46] The church of the Koimesis in Nicaea (present-day Iznik), destroyed in the early on 20th century but documented through photographs, demonstrates the simultaneous survival of a more classical style of church ornamentation.[47] The churches of Rome, nevertheless a Byzantine territory in this period, too include important surviving decorative programs, especially Santa Maria Antiqua, Sant'Agnese fuori le mura, and the Chapel of San Venanzio in San Giovanni in Laterano.[48] Byzantine mosaicists probably likewise contributed to the decoration of the early Umayyad monuments, including the Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem and the Great Mosque of Damascus.[49]

Of import works of luxury art from this period include the silver David Plates, produced during the reign of Emperor Heraclius, and depicting scenes from the life of the Hebrew rex David.[50] The nearly notable surviving manuscripts are Syriac gospel books, such every bit the so-called Syriac Bible of Paris.[51] However, the London Catechism Tables evidence to the continuing product of lavish gospel books in Greek.[52]

The period between Justinian and iconoclasm saw major changes in the social and religious roles of images within Byzantium. The veneration of acheiropoieta, or holy images "not made by human hands," became a significant phenomenon, and in some instances these images were credited with saving cities from military assault. By the end of the seventh century, certain images of saints had come to be viewed as "windows" through which one could communicate with the figure depicted. Proskynesis before images is also attested in texts from the tardily seventh century. These developments mark the beginnings of a theology of icons.[53]

At the same fourth dimension, the debate over the proper part of art in the decoration of churches intensified. Three canons of the Quinisext Council of 692 addressed controversies in this surface area: prohibition of the representation of the cantankerous on church pavements (Catechism 73), prohibition of the representation of Christ equally a lamb (Catechism 82), and a general injunction confronting "pictures, whether they are in paintings or in what way and so ever, which concenter the eye and decadent the mind, and incite information technology to the enkindling of base of operations pleasures" (Canon 100).

Crunch of iconoclasm [edit]

Helios in his chariot, surrounded by symbols of the months and of the zodiac. From Vat. Gr. 1291, the "Handy Tables" of Ptolemy, produced during the reign of Constantine V

Intense argue over the part of fine art in worship led eventually to the menses of "Byzantine iconoclasm."[54] Desultory outbreaks of iconoclasm on the part of local bishops are attested in Asia Modest during the 720s. In 726, an underwater earthquake between the islands of Thera and Therasia was interpreted by Emperor Leo III as a sign of God'due south anger, and may have led Leo to remove a famous icon of Christ from the Chalke Gate outside the imperial palace.[55] However, iconoclasm probably did not become imperial policy until the reign of Leo's son, Constantine 5. The Quango of Hieria, convened under Constantine in 754, proscribed the manufacture of icons of Christ. This inaugurated the Iconoclastic flow, which lasted, with interruptions, until 843.

While iconoclasm severely restricted the role of religious art, and led to the removal of some earlier apse mosaics and (possibly) the sporadic destruction of portable icons, it never constituted a total ban on the production of figural art. Aplenty literary sources indicate that secular art (i.eastward. hunting scenes and depictions of the games in the hippodrome) continued to be produced,[56] and the few monuments that can exist securely dated to the menses (nearly notably the manuscript of Ptolemy's "Handy Tables" today held by the Vatican[57]) demonstrate that metropolitan artists maintained a high quality of production.[58]

Major churches dating to this period include Hagia Eirene in Constantinople, which was rebuilt in the 760s post-obit its destruction by the 740 Constantinople earthquake. The interior of Hagia Eirene, which is dominated past a large mosaic cross in the apse, is ane of the best-preserved examples of iconoclastic church decoration.[59] The church of Hagia Sophia in Thessaloniki was as well rebuilt in the belatedly 8th century.[sixty]

Certain churches congenital outside of the empire during this menses, but decorated in a figural, "Byzantine," way, may too comport witness to the standing activities of Byzantine artists. Particularly important in this regard are the original mosaics of the Palatine Chapel in Aachen (since either destroyed or heavily restored) and the frescoes in the Church of Maria foris portas in Castelseprio.

Macedonian fine art [edit]

The rulings of the Council of Hieria were reversed by a new church council in 843, celebrated to this day in the Eastern Orthodox Church as the "Triumph of Orthodoxy." In 867, the installation of a new alcove mosaic in Hagia Sophia depicting the Virgin and Child was celebrated by the Patriarch Photios in a famous homily as a victory over the evils of iconoclasm. Later in the same year, the Emperor Basil I, called "the Macedonian," acceded to the throne; as a result the post-obit menses of Byzantine fine art has sometimes been chosen the "Macedonian Renaissance", although the term is doubly problematic (it was neither "Macedonian", nor, strictly speaking, a "Renaissance").

In the 9th and tenth centuries, the Empire'southward armed forces situation improved, and patronage of art and architecture increased. New churches were commissioned, and the standard architectural form (the "cross-in-foursquare") and decorative scheme of the Middle Byzantine church were standardised. Major surviving examples include Hosios Loukas in Boeotia, the Daphni Monastery well-nigh Athens and Nea Moni on Chios.

There was a revival of interest in the depiction of subjects from classical Greek mythology (as on the Veroli Casket) and in the use of a "classical" Hellenistic styles to draw religious, and particularly Quondam Attestation, subjects (of which the Paris Psalter and the Joshua Scroll are important examples).

The Macedonian period too saw a revival of the belatedly antiquarian technique of ivory etching. Many ornate ivory triptychs and diptychs survive, such equally the Harbaville Triptych and a triptych at Luton Hoo, dating from the reign of Nicephorus Phocas.

Komnenian age [edit]

The Macedonian emperors were followed by the Komnenian dynasty, beginning with the reign of Alexios I Komnenos in 1081. Byzantium had recently suffered a menstruation of astringent dislocation post-obit the Battle of Manzikert in 1071 and the subsequent loss of Asia Minor to the Turks. Withal, the Komnenoi brought stability to the empire (1081–1185) and during the course of the twelfth century their energetic campaigning did much to restore the fortunes of the empire. The Komnenoi were great patrons of the arts, and with their support Byzantine artists continued to move in the direction of greater humanism and emotion, of which the Theotokos of Vladimir, the cycle of mosaics at Daphni, and the murals at Nerezi yield important examples. Ivory sculpture and other expensive mediums of fine art gradually gave way to frescoes and icons, which for the offset fourth dimension gained widespread popularity across the Empire. Apart from painted icons, there were other varieties - notably the mosaic and ceramic ones.

Some of the finest Byzantine work of this period may be constitute exterior the Empire: in the mosaics of Gelati, Kiev, Torcello, Venice, Monreale, Cefalù and Palermo. For case, Venice's Basilica of St Marking, begun in 1063, was based on the great Church building of the Holy Apostles in Constantinople, now destroyed, and is thus an echo of the historic period of Justinian. The avaricious habits of the Venetians mean that the basilica is likewise a great museum of Byzantine artworks of all kinds (e.k., Pala d'Oro).

Ivory caskets of the Macedonian era (Gallery) [edit]

-

-

11th-twelfth century, Museo Nazionale d'Arte Medievale due east Moderna (Arezzo)

Palaeologan historic period [edit]

![]()

The Announcement from Ohrid, one of the well-nigh admired icons of the Paleologan mannerism, bears comparing with the finest contemporary works by Italian artists

Centuries of continuous Roman political tradition and Hellenistic civilisation underwent a crisis in 1204 with the sacking of Constantinople by the Venetian and French knights of the Quaternary Crusade, a disaster from which the Empire recovered in 1261 albeit in a severely weakened state. The destruction by sack or subsequent neglect of the city'south secular architecture in detail has left usa with an imperfect agreement of Byzantine fine art.

Although the Byzantines regained the city in 1261, the Empire was thereafter a small-scale and weak state confined to the Greek peninsula and the islands of the Aegean. During their half-century of exile, however, the concluding great flowing of Anatolian Hellenism began. As Nicaea emerged as the middle of opposition under the Laskaris emperors, it spawned a renaissance, attracting scholars, poets, and artists from across the Byzantine world. A glittering court emerged equally the dispossessed intelligentsia constitute in the Hellenic side of their traditions a pride and identity unsullied by association with the hated "latin" enemy.[61] With the recapture of the capital under the new Palaeologan Dynasty, Byzantine artists developed a new interest in landscapes and pastoral scenes, and the traditional mosaic-work (of which the Chora Church building in Constantinople is the finest extant instance) gradually gave way to detailed cycles of narrative frescoes (every bit evidenced in a large group of Mystras churches). The icons, which became a favoured medium for artistic expression, were characterized past a less austere mental attitude, new appreciation for purely decorative qualities of painting and meticulous attention to details, earning the popular name of the Paleologan Mannerism for the menstruation in full general.

Venice came to control Byzantine Crete by 1212, and Byzantine artistic traditions connected long after the Ottoman conquest of the last Byzantine successor state in 1461. The Cretan schoolhouse, as information technology is today known, gradually introduced Western elements into its fashion, and exported large numbers of icons to the West. The tradition's most famous artist was El Greco.[62] [63]

Legacy [edit]

The splendour of Byzantine art was e'er in the mind of early on medieval Western artists and patrons, and many of the near important movements in the menses were conscious attempts to produce art fit to stand next to both classical Roman and gimmicky Byzantine art. This was especially the example for the imperial Carolingian fine art and Ottonian art. Luxury products from the Empire were highly valued, and reached for instance the royal Anglo-Saxon Sutton Hoo burying in Suffolk of the 620s, which contains several pieces of argent. Byzantine silks were especially valued and large quantities were distributed equally diplomatic gifts from Constantinople. There are records of Byzantine artists working in the West, especially during the catamenia of iconoclasm, and some works, like the frescos at Castelseprio and miniatures in the Vienna Coronation Gospels, seem to have been produced by such figures.

In item, teams of mosaic artists were dispatched every bit diplomatic gestures past emperors to Italy, where they ofttimes trained locals to continue their piece of work in a style heavily influenced by Byzantium. Venice and Norman Sicily were detail centres of Byzantine influence. The earliest surviving console paintings in the Due west were in a style heavily influenced by contemporary Byzantine icons, until a distinctive Western manner began to develop in Italia in the Trecento; the traditional and however influential narrative of Vasari and others has the story of Western painting brainstorm every bit a breakaway by Cimabue and then Giotto from the shackles of the Byzantine tradition. In general, Byzantine artistic influence on Europe was in steep refuse by the 14th century if not earlier, despite the continued importance of migrated Byzantine scholars in the Renaissance in other areas.

Islamic art began with artists and craftsmen mostly trained in Byzantine styles, and though figurative content was greatly reduced, Byzantine decorative styles remained a groovy influence on Islamic art, and Byzantine artists continued to be imported for important works for some time, especially for mosaics.

The Byzantine era properly defined came to an end with the fall of Constantinople to the Ottoman Turks in 1453, merely past this fourth dimension the Byzantine cultural heritage had been widely diffused, carried past the spread of Orthodox Christianity, to Republic of bulgaria, Serbia, Romania and, most importantly, to Russian federation, which became the centre of the Orthodox earth following the Ottoman conquest of the Balkans. Even nether Ottoman rule, Byzantine traditions in icon-painting and other small-scale-scale arts survived, especially in the Venetian-ruled Crete and Rhodes, where a "post-Byzantine" style nether increasing Western influence survived for a further two centuries, producing artists including El Greco whose training was in the Cretan School which was the most vigorous post-Byzantine school, exporting great numbers of icons to Europe. The willingness of the Cretan School to accept Western influence was atypical; in most of the postal service-Byzantine world "as an instrument of indigenous cohesiveness, art became assertively bourgeois during the Turcocratia" (catamenia of Ottoman rule).[64]

Russian icon painting began by entirely adopting and imitating Byzantine art, as did the art of other Orthodox nations, and has remained extremely conservative in iconography, although its painting mode has developed distinct characteristics, including influences from postal service-Renaissance Western art. All the Eastern Orthodox churches accept remained highly protective of their traditions in terms of the form and content of images and, for example, modern Orthodox depictions of the Birth of Christ vary piddling in content from those developed in the sixth century.

Run across also [edit]

- Byzantine illuminated manuscripts

- Byzantine architecture

- Byzantine mosaics

- Macedonian fine art (Byzantine)

- Byzantine Iconoclasm

- Sacred art

- Book of Chore in Byzantine Illuminated Manuscripts

Notes [edit]

- ^ Michelis 1946; Weitzmann 1981.

- ^ Kitzinger 1977, pp. i‒3.

- ^ Michelis 1946; Ainalov 1961, "Introduction", pp. three‒8; Stylianou & Stylianou 1985, p. xix; Hanfmann 1962, "Early Christian Sculpture", p. 42 harvnb mistake: no target: CITEREFHanfmann1962 (help); Weitzmann 1984.

- ^ Bassett 2004.

- ^ Cyril 1965, pp. 53‒75 harvnb mistake: no target: CITEREFCyril1965 (help).

- ^ Ainalov 1961, "The Hellenistic Character of Byzantine Wall Painting", pp. 185‒214.

- ^ Weitzmann 1981, p. 350.

- ^ Brendel 1979.

- ^ Berenson 1954.

- ^ Elsner 2002, pp. 358‒379.

- ^ Kitzinger 1977.

- ^ Onians 1980, pp. ane‒23.

- ^ Mango 1963, p. 65.

- ^ Belting & Jephcott 1994 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFBeltingJephcott1994 (aid).

- ^ Bassett 2004.

- ^ Fowden 1991, pp. 119‒131; Bauer 1996.

- ^ Mathews 1971; Henck 2001, pp. 279‒304

- ^ Kiilerich 1998.

- ^ Mathews 1971.

- ^ Krautheimer 2000.

- ^ Spieser 1984; Ćurčić 2000.

- ^ Wright 1993.

- ^ Wright 2001.

- ^ Levin 1985.

- ^ Volbach 1976.

- ^ Delbrueck 1929.

- ^ Dodd 1961.

- ^ Almagro-Gorbea 2000.

- ^ Maas 2005.

- ^ Tr. H.B. Dewing, Procopius VII (Cambridge, 1962).

- ^ Mainstone 1997.

- ^ Night & Özgümüş 2002, pp. 393‒413.

- ^ Bardill 2000, pp. 1‒11; Mathews 2005.

- ^ Forsyth & Weitzmann 1973.

- ^ Thiel 2005.

- ^ Deichmann 1969.

- ^ Eufrasiana Basilica Projection.

- ^ Wellesz 1960.

- ^ Cavallo 1992.

- ^ Grabar 1948.

- ^ Mazal 1998.

- ^ Cutler 1993, pp. 329‒339.

- ^ Wright 1986, pp. 75‒79.

- ^ photo of the plate

- ^ Haldon 1997.

- ^ Brubaker 2004, pp. 63‒90.

- ^ Barber 1991, pp. 43‒threescore.

- ^ Matthiae 1987.

- ^ Creswell 1969; Flood 2001.

- ^ Leader 2000, pp. 407‒427.

- ^ Leroy 1964.

- ^ Nordenfalk 1938.

- ^ Brubaker 1998, pp. 1215‒1254.

- ^ Bryer & Herrin 1977; Brubaker & Haldon 2001.

- ^ Stein 1980; The story of the Chalke Icon may be a afterwards invention: Auzépy 1990, pp. 445‒492.

- ^ Grabar 1984.

- ^ Wright 1985, pp. 355‒362.

- ^ Bryer & Herrin 1977, Robin Cormack, "The Arts during the Age of Iconoclasm".

- ^ Peschlow 1977.

- ^ Theocharidou 1988.

- ^ Ash 1995.

- ^ Byron, Robert (October 1929). "Greco: The Epilogue to Byzantine Culture". The Burlington Magazine for Connoisseurs. 55 (319): 160–174. JSTOR 864104.

- ^ Procopiou, Angelo K. (March 1952). "El Greco and Cretan Painting". The Burlington Magazine. 94 (588): 76–74. JSTOR 870678.

- ^ Kessler 1988, p. 166.

References [edit]

- Ainalov, D.V. (1961). The Hellenistic Origins of Byzantine Art. New Brunswick: Rutgers Academy Printing.

- Almagro-Gorbea, K., ed. (2000). El Disco de Teodosio. Madrid: Real Academia de la Historia. ISBN9788489512603.

- Ash, John (1995). A Byzantine Journey . London: Random House Incorporated. ISBN9780679409342.

- Auzépy, M.-F. (1990). "La destruction de l'icône du Christ de la Chalcé par Léon III: propagande ou réalité?". Byzantion. sixty: 445‒492.

- Barber, C. (1991). "The Koimesis Church building, Nicaea: The Limits of Representation on the Eve of Iconoclasm". Jahrbuch der österreichischen Byzantinistik. 41: 43‒threescore.

- Bardill, J. (2000). "The Church of Sts. Sergius and Bacchus in Constantinople and the Monophysite Refugees". Dumbarton Oaks Papers. 54: 1‒11. doi:10.2307/1291830. JSTOR 1291830.

- Bassett, Sarah (2004). The Urban Image of Late Antique Constantinople. Cambridge: Cambridge Academy Press. ISBN9780521827232.

- Bauer, Franz Alto (1996). Stadt, Platz und Denkmal in der Spätantike. Mainz: P. von Zabern. ISBN9783805318426.

- Belting, Hans; Jephcott (tr.), Edmund (1994). Likeness and Presence: A History of the Epitome before the Era of Art. Chicago: Chicago University Press. ISBN9780226042152.

- Berenson, Bernard (1954). The Arch of Constantine, or, the Decline of Course. London: Chapman and Hall.

- Brendel, Otto J. (1979). Prolegomena to the Study of Roman Art . New Haven: Yale University Printing. ISBN9780300022681.

- Brubaker, Leslie; Haldon, John (2001). Byzantium in the Iconoclast Era (ca. 680-850): The Sources. Birmingham: Ashgate.

- Brubaker, L. (1998). "Icons before iconoclasm?, Morfologie sociali e culturali in europa fra tarda antichita e alto medioevo". Settimane di Studio del Centro Italiano di Studi Sull' Alto Medioevo. 45: 1215‒1254.

- Brubaker, L. (2004). "Elites and Patronage in Early Byzantium: The Evidence from Hagios Demetrios in Thessalonike". In Haldon, John; et al. (eds.). The Byzantine and Early Islamic Most East: Elites Old and New. Princeton: Princeton University Press. pp. 63‒90.

- Bryer, A.; Herrin, Judith, eds. (1977). Iconoclasm: Papers Given at the Ninth Jump Symposium of Byzantine Studies, Academy of Birmingham, March 1975. Birmingham: Center for Byzantine Studies. ISBN9780704402263.

- Cavallo, Guglielmo (1992). Il codex purpureus rossanensis. Rome.

- Creswell, Keppel A.C. (1969). Early Muslim Architecture. New York: Clarendon Press.

- Ćurčić, Slobodan (2000). Some Observations and Questions Regarding Early on Christian Compages in Thessaloniki. Thessaloniki: Υπουργείον Πολιτισμού: Εφορεία Βυζαντινών Αρχαιοτήτων Θεσσαλονίκης. ISBN9789608674905.

- Cutler, A. (1993). "Barberiniana: Notes on the Making, Content, and Provenance of Louvre OA. 9063". Tesserae: Festschrift für Josef Engemann, Jahrbuch für Antike und Christentum, Ergänzungsband. 18: 329‒339.

- Nighttime, K.; Özgümüş, F. (2002). "New Prove for the Byzantine Church of the Holy Apostles from Fatih Camii, Istanbul". Oxford Periodical of Archaeology. 21 (four): 393‒413. doi:x.1111/1468-0092.00170.

- Deichmann, Friedrich Wilhelm (1969). Ravenna: Hauptstadt des spätantiken Abendlandes. Wiesbaden: Franz Steiner. ISBN9783515020053.

- Delbrueck, R. (1929). Die Consulardiptychen und Verwandte Denkmäler. Berlin: De Gruyter.

- Dodd, Erica Cruikshank (1961). Byzantine Argent Stamps. Washington: Dumbarton Oaks Inquiry Library and Drove, Trustees for Harvard Academy.

- Elsner, J. (2002). "The Birth of Late Antiquity: Riegl and Strzygowski in 1901". Art History. 25 (3): 358‒379. doi:10.1111/1467-8365.00326.

- Ene D-Vasilescu, Elena (2021). Michelangelo, the Byzantines, and Plato. ISBN9781800498792.

- Ene D-Vasilescu, Elena (2021). Glimpses into Byzantium. Its Philosophy and Arts. ISBN9781800498808.

- Flood, Finbarr Barry (2001). The Cracking Mosque of Damascus: Studies on the Making of an Umayyad Visual Culture. Leiden: Brill.

- Forsyth, George H.; Weitzmann, Kurt (1973). The Monastery of St. Catherine at Mount Sinai: The Church and Fortress of Justinian. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

- Fowden, Garth (1991). "Constantine's Porphyry Column: The Earliest Literary Innuendo". Journal of Roman Studies. 81: 119‒131. doi:10.2307/300493. JSTOR 300493.

- Grabar, André (1984). L'iconoclasme byzantin: Le dossier archéologique (second ed.). Paris: Flammarion. ISBN9782080126030.

- Grabar, André (1948). Les peintures de l'évangéliaire de Sinope (Bibliothèque nationale, Suppl. gr. 1286). Paris: Bibliothèque nationale.

- Haldon, John (1997) [1990]. Byzantium in the Seventh Century: The Transformation of a Culture. Cambridge: Cambridge Academy Press.

- Hanfmann, George Maxim Anossov (1967). Classical Sculpture. Greenwich, CT: New York Graphic Society.

- Henck, N. (2001). "Constantius ho Philoktistes?" (PDF). Dumbarton Oaks Papers. 55: 279‒304. doi:10.2307/1291822. JSTOR 1291822. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-05-12. Retrieved 2014-09-29 .

- Kessler, Herbert L. (1988). "On the State of Medieval Art History". The Fine art Bulletin. 70 (2): 166–187. doi:10.1080/00043079.1988.10788561. JSTOR 3051115.

- Kiilerich, Bente (1998). The Obelisk Base in Constantinople. Rome: G. Bretschneider.

- Kitzinger, Ernst (1977). Byzantine Art in the Making: Main Lines of Stylistic Evolution in Mediterranean Art, tertiary‒7th Century. Cambridge: Cambridge Academy Press. ISBN978-0571111541.

- Krautheimer, R. (2000). Rome: Profile of a Metropolis. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN9780691049618.

- Leader, R. (2000). "The David Plates Revisited: Transforming the Secular in Early Byzantium". Fine art Message. 82 (3): 407‒427. doi:10.2307/3051395. JSTOR 3051395.

- Leroy, Jules (1964). Les manuscrits syriaques à peintures conservés dans les bibliothèques d'Europe et d'Orient; contribution à l'étude de l'iconographie des Églises de langue syriaque. Paris: Librairie orientaliste P. Geuthner.

- Levin, I. (1985). The Quedlinburg Itala: The Oldest Illustrated Biblical Manuscript. Leiden: E.J. Brill. ISBN9789004070936.

- Maas, Chiliad., ed. (2005). The Cambridge Companion to the Age of Justinian. Cambridge: Cambridge Academy Press. ISBN9781139826877.

- Mainstone, Rowland J. (1997). Hagia Sophia: Architecture, Structure, and Liturgy of Justinian's Great Church. New York: Thames and Hudson. ISBN9780500279458.

- Mango, Cyril (1963). "Antique Statuary and the Byzantine Beholder". Dumbarton Oaks Papers. 17: 53‒75. doi:10.2307/1291190. JSTOR 1291190.

- Mathews, Thomas F. (1971). The Early Churches of Constantinople: Compages and Liturgy. University Park: Pennsylvania State Academy Printing. ISBN9780271001081.

- Mathews, Thomas F. (2005). "The Palace Church building of Sts. Sergius and Bacchus in Constantinople". In Emerick, J.J.; Delliyannis, D.M. (eds.). Archaeology in Compages: Studies in Honor of Cecil Fifty. Striker. Mainz: von Zabern. ISBN9783805334921.

- Matthiae, Guglielmo (1987). Pittura romana del medioevo. Rome: Fratelli Palombi. ISBN9788876212345.

- Mazal, Otto (1998). Der Wiener Dioskurides: Codex medicus Graecus 1 der Österreichischen Nationalbibliothek. Graz: Akademische Druck u. Verlagsanstalt. ISBN9783201016995.

- Michelis, Panayotis A. (1946). An Aesthetic Approach to Byzantine Fine art. Athens.

- Nordenfalk, Carl (1938). Die spätantiken Kanontafeln. Göteborg: O. Isacsons boktryckeri a.-b.

- Onians, J. (1980). "Abstraction and Imagination in Late Antiquity". Art History. 3: 1‒23. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8365.1980.tb00061.x.

- Peschlow, Urs (1977). Die Irenenkirche in Istanbul. Tübingen: E. Wasmuth. ISBN9783803017178.

- Runciman, Steven (1987) [1954]. A History of the Crusades: The Kingdom of Acre and the Later on Crusades. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN978-0521347723.

- Spieser, J.-Chiliad. (1984). Thessalonique et ses monuments du IVe au VIe siècle. Athens: Ecole française d'Athènes.

- Stein, D. (1980). Der Beginn des byzantinischen Bilderstreites und seine Entwicklung bis in die 40er Jahre des eight. Jahrhunderts. Munich: Institut für Byzantinistik und Neugriechische Philologie der Universität.

- Stylianou, Andreas; Stylianou, Judith A. (1985). The Painted Churches of Cyprus: Treasures of Byzantine Art. London: Trigraph for the A.G. Leventis Foundation.

- Theocharidou, K. (1988). The Architecture of Hagia Sophia, Thessaloniki, from its Erection upwards to the Turkish Conquest. Oxford: Oxford University Printing.

- Thiel, Andreas (2005). Die Johanneskirche in Ephesos. Wiesbaden: Isd. ISBN9783895003547.

- Volbach, Wolfgang Fritz (1976). Elfenbeinarbeiten der Spätantike und des frühen Mittelalters. Mainz: von Zabern. ISBN9783805302807.

- Weitzmann, Kurt (1981). Classical Heritage in Byzantine and Nearly Eastern Art. London: Variorum Reprints.

- Weitzmann, Kurt (1984). Greek Mythology in Byzantine Fine art. Princeton: Princeton University Printing. ISBN9780860780878.

- Wellesz, Emmy (1960). The Vienna Genesis. London: T. Yoseloff.

- Wright, D. H. (1985). "The Date of the Vatican Illuminated Handy Tables of Ptolemy and of its Early on Additions". Byzantinische Zeitschrift. 78 (two): 355‒362. doi:10.1515/byzs.1985.78.2.355. S2CID 194111177.

- Wright, D. (1986). "Justinian and an Archangel". Studien zur Spätantiken Kunst Friedrich Wilhelm Deichmann Gewidmet. Mainz. Iii: 75‒79.

- Wright, David Herndon (2001). The Roman Vergil and the Origins of Medieval Volume Design. Toronto: Academy of Toronto Press. ISBN9780802048196.

- Wright, David Herndon (1993). The Vatican Vergil: A Masterpiece of Late Antique Art. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN9780520072404.

Further reading [edit]

- Alloa, Emmanuel (2013). "Visual Studies in Byzantium". Periodical of Visual Civilization. 12 (1): 3‒29. doi:10.1177/1470412912468704. S2CID 191395643.

- Beckwith, John (1979). Early Christian and Byzantine Art (second ed.). Penguin History of Art. ISBN978-0140560336.

- Cormack, Robin (2000). Byzantine Art . Oxford: Oxford Academy Press. ISBN978-0-xix-284211-iv.

- Cormack, Robin (1985). Writing in Golden, Byzantine Society and its Icons. London: George Philip. ISBN978-054001085-1.

- Eastmond, Antony (2013). The Glory of Byzantium and Early on Christendom. London: Phaidon Press. ISBN978-0714848105.

- Evans, Helen C., ed. (2004). Byzantium, Faith and Power (1261‒1557) . Metropolitan Museum of Art/Yale University Press. ISBN978-1588391148.

- Evans, Helen C. & Wixom, William D. (1997). The Celebrity of Byzantium: Art and Civilization of the Middle Byzantine Era, A.D. 843‒1261. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. OCLC 853250638.

- Hurst, Ellen (8 August 2014). "A Beginner'south Guide to Byzantine Art". Smarthistory. Retrieved 20 Apr 2016.

- James, Elizabeth (2007). Art and Text in Byzantine Civilisation (1 ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN978-0-521-83409-4.

- Karahan, Anne (2015). "Patristics and Byzantine Meta-Images. Molding Conventionalities in the Divine from Written to Painted Theology". In Harrison, Carol; Bitton-Ashkelony, Brouria; De Bruyn, Théodore (eds.). Patristic Studies in the Twenty-Start Century. Turnhout: Brepols Publishers. pp. 551–576. ISBN978-ii-503-55919-3.

- Karahan, Anne (2010). Byzantine Holy Images – Transcendence and Immanence. The Theological Background of the Iconography and Aesthetics of the Chora Church (Orientalia Lovaniensia Analecta No. 176). Leuven-Paris-Walpole, MA: Peeters Publishers. ISBN978-xc-429-2080-4.

- Karahan, Anne (2016). "Byzantine Visual Culture. Conditions of "Right" Belief and some Platonic Outlooks"". Numen: International Review for the History of Religions. Leiden: Koninklijke Brill NV. 63 (2–iii): 210–244. doi:x.1163/15685276-12341421. ISSN 0029-5973.

- Karahan, Anne (2014). "Byzantine Iconoclasm: Ideology and Quest for Power". In Kolrud, K.; Prusac, M. (eds.). Iconoclasm from Antiquity to Modernity. Farnham Surrey: Ashgate Publishing Ltd. pp. 75‒94. ISBN978-1-4094-7033-5.

- Karahan, Anne (2015). "Affiliate x: The Impact of Cappadocian Theology on Byzantine Aesthetics: Gregory of Nazianzus on the Unity and Singularity of Christ". In Dumitraşcu, N. (ed.). The Ecumenical Legacy of the Cappadocians. New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 159‒184. ISBN978-1-137-51394-half dozen.

- Karahan, Anne (2012). "Beauty in the Optics of God. Byzantine Aesthetics and Basil of Caesarea". Byzantion: Revue Internationale des Études Byzantines. 82: 165‒212. eISSN 2294-6209. ISSN 0378-2506. *Karahan, Anne (2013). "The Image of God in Byzantine Cappadocia and the Event of Supreme Transcendence". Studia Patristica. 59: 97‒111. ISBN978-90-429-2992-0.

- Karahan, Anne (2010). "The Result of περιχώρησις in Byzantine Holy Images". Studia Patristica. 44: 27‒34. ISBN978-90-429-2370-6.

- Gerstel, Sharon E. J.; Lauffenburger, Julie A., eds. (2001). A Lost Art Rediscovered. Pennsylvania State University. ISBN978-0-271-02139-3.

- Mango, Cyril, ed. (1972). The Art of the Byzantine Empire, 312‒1453: Sources and Documents. Englewood Cliffs.

- Obolensky, Dimitri (1974) [1971]. The Byzantine Commonwealth: Eastern Europe, 500‒1453. London: Fundamental. ISBN9780351176449.

- http://world wide web.biblionet.gr/volume/178713/Ανδρέου,_Ευάγγελος/Γεώργιος_Μάρκου_ο_ΑργείοςWeitzmann, Kurt, ed. (1979). Age of Spirituality: Late Antiquarian and Early Christian Art, Third to Seventh Century. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

External links [edit]

- Byzantine Publications Online, freely bachelor for download from Dumbarton Oaks

- Lethaby, William (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. four (11th ed.). pp. 906–911.

- Eikonografos.com: Byzantine Icons and Mosaics Archived 2012-03-31 at the Wayback Machine

- Anthony Cutler on the economic history of Byzantine mosaics, wall-paintings and icons at Dumbarton Oaks.

- http://www.biblionet.gr/book/178713/Ανδρέου,_Ευάγγελος/Γεώργιος_Μάρκου_ο_Αργείος

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Byzantine_art

0 Response to "Byzantine Art in General Could Be Said to Be in Relation to Christian Art"

Post a Comment